Nutrient Pollution

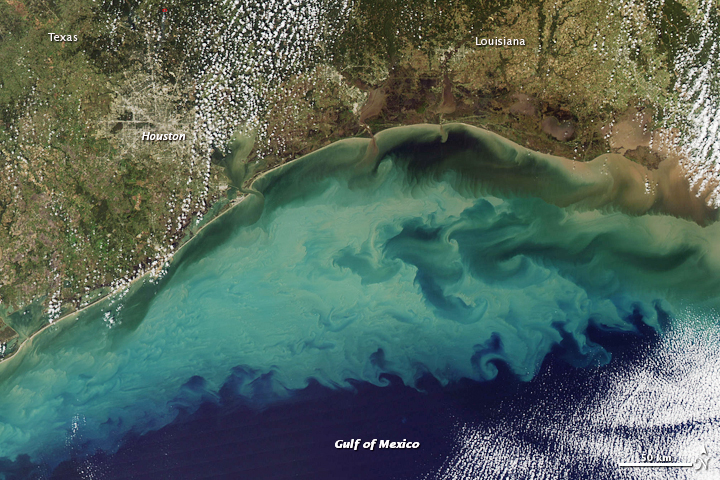

Reducing nutrient pollution is vitally important

for protecting human health, river ecosystems and the Gulf of Mexico

GREAT LAKES

The Great Lakes is the largest freshwater ecosystem on Earth

infrastructure

Illinois's water resources face many infrastructure challenges

nutrient pollution

Nitrogen & phosphorus pollution degrade our water

drinking water

Lead in drinking water threatens many IL communities

Nutrient Pollution and Algal Blooms

The effects of algae overgrowth are felt throughout Illinois. Results from 13 Illinois water bodies sampled in 2012 indicate that cyanobacteria and associated cyanotoxins are a concern for Illinois residents — 10 of the 13 water bodies indicated a high probability of acute health effects during recreational exposure from cyanobacteria, and one had a very high probability.

Current Nutrient Pollution Laws

The primary federal law governing water pollution, with the objective of restoring and maintaining the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation’s waters by preventing pollution, providing for the improvement of wastewater treatment, and maintaining the integrity of wetlands. Under the CWA, states have the “primary responsibilities and rights” to achieve the Act’s objectives, overseen by the U.S. EPA. Absent adequate state administration, the EPA establishes criteria for water quality, determines discharge levels, issues and enforces permits, and will take over if it determines that the state is underperforming.

Issued in 1998, the Plan directed EPA to develop acceptable levels of nitrogen and phosphorus for all water body types and ecoregions in the country. Individual states were originally required to adopt water quality standards for these nutrients, but Illinois has not even developed a work plan for nutrient criteria for streams where nitrogen and phosphorous start their journeys.

The Livestock Management Facilities Act

Adopted in 1996, this Illinois law establishes requirements for the siting, design, and construction of livestock management and livestock waste-handling facilities. This Act is administered by the Department of Agriculture. Under the Act, any newly-proposed livestock management facility, and certain expanding livestock management facilities, must receive a permit from the Department of Agriculture to build or expand. However, the Act has been criticized for not having a meaningful public participation process for the siting of new and expanding facilities.

A livestock management facility permit from the Department of Agriculture is, in essence, a construction permit. After a facility is built, the IEPA becomes the regulatory agency responsible for ensuring it is operated responsibly. Because the IEPA does not require NPDES permits for most CAFOs or other operating permits for CAFOs, the management and disposal of animal waste from CAFOs is largely unregulated in Illinois even though livestock animals produce exponentially more waste than humans. The U.S. EPA blames CAFOs for 20% of all pollution in rivers, lakes, and streams.

Regulation of Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations

After a two-year investigation in response to a citizen petition filed by the Illinois Citizens for Clean Air & Water (ICCAW), the U.S. EPA determined that Illinois was failing to protect waterways from CAFO pollutants. As a result, the Illinois Pollution Control Board (IPCB) promulgated new rules for CAFOs in Illinois, effective in 2014. However, NPDES permits are still not required for any CAFO that doesn’t claim to discharge or isn’t designed to discharge pollutants. For example, a facility that uses lagoons that aren’t designed to flow into waterways may be exempt from NPDES permitting.

While the new IPCB CAFO rules for waste handling and management are much more stringent than the rules that were in place previously, the new regulations only apply to permitted CAFOs. Therefore, since a vast majority of CAFOs in Illinois claim to be “zero discharge” facilities that do not have permits, the improved regulations only apply to a very small percentage of CAFO operations.

Buffer Rule for Livestock

In Illinois, livestock waste may not be applied within 100 feet of down-gradient open subsurface drainage intakes, agricultural drainage wells, sinkholes, waterways or other conduits to surface waters, without an existing 35 foot vegetative buffer between the application area and waterways or conduits to surface water. A vegetative buffer is a strip of land covered with perennial vegetation, meant to intercept nutrients and other water pollutants before they reach water.

Passed in 2010, prohibits the use of phosphorus in dish detergents.

The 2015 strategy was developed in response to the U.S. EPA 2008 Gulf Hypoxia Action Plan, which calls for each of the 12 states in the Mississippi River Basin to produce a plan to reduce the amount of phosphorus and nitrogen carried in rivers throughout the states and to the Gulf of Mexico. It calls for Illinois to voluntarily reduce its output of nitrogen and phosphorus each by 45%.

NREC was established in 2012 to support science-based research and outreach programs designed to measure the impact of environmental and management factors affecting nutrient reactions in the soil and utilization of nutrients by plants. The results from these programs provide farmers with information to design production systems for their conditions that minimize environmental impact, optimize harvest yield, and maximize nutrient utilization.

Clean Water Updates

Protected: Illinois’ Role in Great Lakes Protection

There is no excerpt because this is a protected post.

Read More >>2025 Legislative Report

IEC's state legislative team has published our 2024 Legislative Report detailing environmental wins and setbacks during this year's legislative session.

Read More >>As Chicagoans Brace for Higher Water Bills, Groups Push for Affordability Reforms

Water rates have more than doubled since 2010. Low-income residents feel the pinch most of all. On Sunday Chicagoans will face another spike in their...

Read More >>On Earth Day, EPA union workers decry cuts to clean air and water regulations

Fifty-five years after the first Earth Day, Environmental Protection Agency employees and advocates call for help as the Trump administration rolls back environmental regulations and...

Read More >>Illinois Has Your Back, Mother Earth

We can’t count on Washington to do right for the environment. Good thing Illinois’ environmental movement is on top of it.

Read More >>Illinois’ Gardens Fight Climate Change

The Homeowner's Native Landscaping Act, passed into law in 2024, is a win for Illinois' biodiversity and climate.

Read More >>